Two Graphics You Should Know Before the 2023 Growing Season

This article originally appeared in the AGVISE Laboratories Spring 2023 Newsletter

The goal of AGVISE Newsletters is to inform you and your customers of important soil fertility information relevant to our area. Often, visuals or graphs are much more powerful at communicating a message than words. With that in mind, I want to share two figures I think you should know about going into the 2023 growing season with a short synopsis and where you can find more information on the topic.

Adapted from the “Biostimulants” episode of the University of Minnesota Extension Nutrient Management Podcast https://nutrientmanagement.transistor.fm/episodes/biostimulants-52305fc9-6c01-4907-8507-2bcf4c708a08

Adapted from the “Biostimulants” episode of the University of Minnesota Extension Nutrient Management Podcast https://nutrientmanagement.transistor.fm/episodes/biostimulants-52305fc9-6c01-4907-8507-2bcf4c708a08

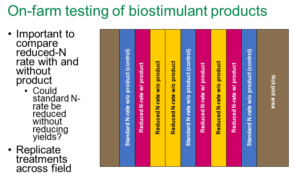

Right now, there are many biological products and fertilizer additives on the market. In particular, asymbiotic nitrogen-fixing products have gained a lot of attention, but many have little or no university research evaluating them. Any grower wanting to try new products should test them on a small acreage first, before adopting them across the whole farm. To the left is a diagram of how such an on-farm trial would look. The key factors of a meaningful on-farm trial include a control treatment (the standard practice), the standard practice plus the product, and randomized replication (at least three replicates, randomized so that one treatment is not always on the east or west side of the trial area).

If the standard nitrogen rate will be reduced when the product is used, a treatment should also be included that compares the same reduced nitrogen rate without the product (this three-treatment setup is what is pictured). If the standard nitrogen rate is higher than the crop N requirement, maybe if you do not have a current soil nitrate-N test or just general overapplication, a reduced nitrogen rate plus the product that produces the same crop yield as the standard practice does not mean that the product is producing additional nitrogen for the crop; it may just mean that the grower can cut back their standard nitrogen rate.

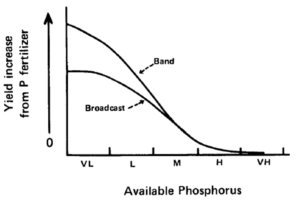

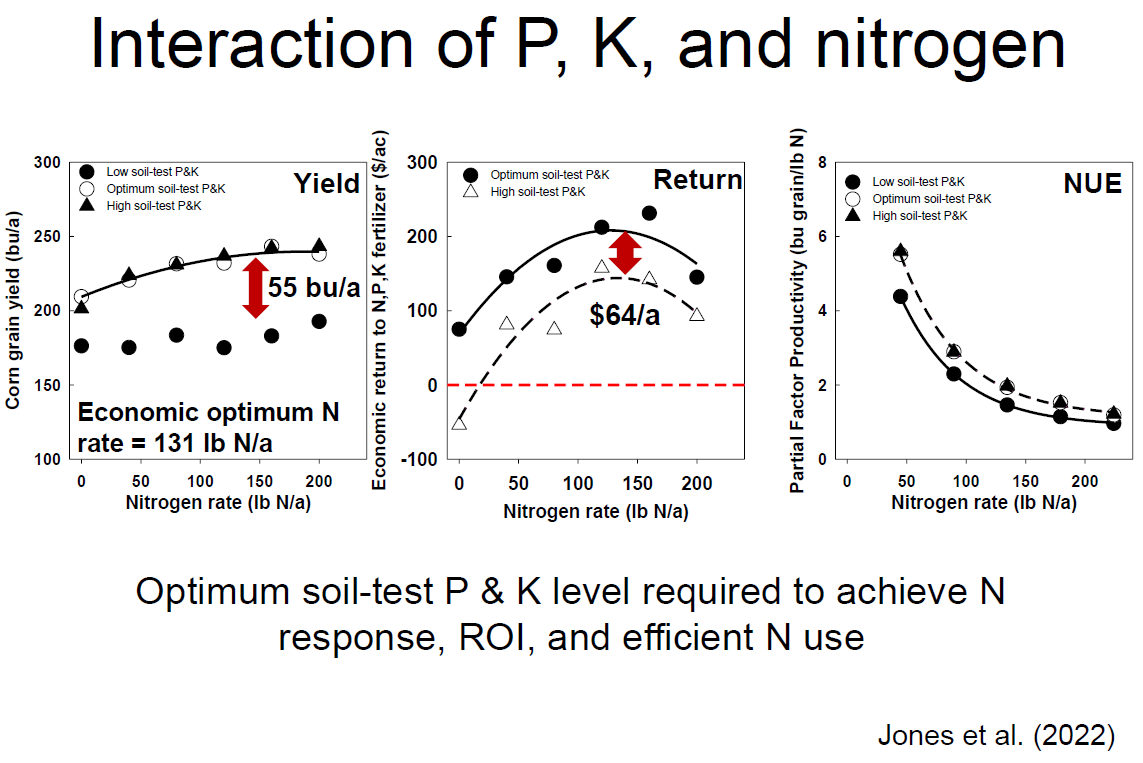

Slide from Dr. John Jones’ 2023 AGVISE Seminar presentation, Phosphorus and Potassium: A Fresh Look with Fresh Data https://www.agvise.com/resources/seminars-and-events/

With fertilizer prices remaining high, it is tempting to cut back phosphorus and potassium inputs to save money. As tempting as this is, do not cut back farther than the fertilizer rates needed to meet the critical soil test level, as optimum soil-test P and K levels are required to achieve the highest response from nitrogen fertilizer. While working to update the Wisconsin phosphorus and potassium fertilizer guidelines, Dr. John Jones at the University of Wisconsin has put together some excellent data illustrating the reality of Liebig’s Law of the Minimum: when P and K fertility needs are unmet, the return from nitrogen fertilizer investment will be reduced compared to when P and K are at optimum levels. This means pouring on more nitrogen will not increase crop yield unless you are doing a good job of managing P and K too. Although not shown here, Dr. Jones also has data showing that corn and soybean yield response to P is reduced when K fertility needs are unmet.