Potassium is back on the radar for many farmers and agronomists across the upper Midwest and northern Great Plains. In the past two weeks, corn growth and development have reached the stage where potassium deficiencies are becoming quite apparent, and widespread dry soil conditions during the 2021 drought have worsened the problem. In some instances, corn is displaying potassium deficiency symptoms on soils with medium to high soil test K (120 to 180 ppm) in spite of potassium fertilizer application.

Potassium is required in large quantities for plant growth and development. The plant tissue K range in normal corn plants is 3-5% K, which is similar to nitrogen. A 200-bushel/acre corn crop will typically uptake 200 lb N, 108 lb P2O5, and 280 lb K2O per acre through the growing season (IPNI, 2014). In other words, an actively growing corn crop takes a lot of potassium! Luckily, you do not have to apply all that potassium as fertilizer, and much will come from the plant-available K pool in the soil.

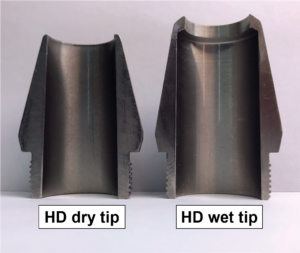

Potassium deficiency in corn. Symptoms are leaf chlorosis (yellowing) and necrosis (death) beginning at the leaf tip and outer leaf margin and progressing toward the midrib, often with wavy leaf edges. Potassium is mobile in the plant, so symptoms appear on the lower leaves first as the plant remobilizes potassium from lower leaves to support new plant growth.

Drought reduces potassium availability

The plant-available K pool becomes less available when soil water is limited. This has become the top story as the 2021 drought has continued. Plant roots acquire potassium mostly through a process called diffusion. Diffusion is the slow movement of ions through water around soil particles to the plant root for uptake. As soil becomes drier, the thickness of the water film around soil particles becomes thinner and thinner, thus the diffusion path for potassium ions becomes longer and longer. The soil pore space becomes mostly air with little water remaining. This ultimately slows the rate at which potassium from soil or fertilizer can reach the plant root, and potassium deficiency may occur.

The consequence of the drought-induced potassium deficiency is two-fold because potassium also plays an essential role in plant water regulation. Potassium-stressed plants experience reduced photosynthesis and transpiration rates, resulting in poor water use efficiency of the already limited soil water that is available. In a nutshell, low soil water content reduces potassium availability from soil and fertilizer, and then the soil water that is there is poorly utilized because of the lack of potassium. In addition to limited soil water, other factors compound to reduce potassium uptake: soil test K, soil texture, clay mineralogy, soil compaction, and even fluffy soil syndrome.

Believe it or not, fluffy soil syndrome has been a component of more than one phone call concerning potassium deficiency. Do you see greener plants near the planter wheel tracks or sprayer tracks? Fluffy soil syndrome occurs when soil has not completely settled since spring tillage, which results in poor soil particle-to-particle contact and slow soil-water-root diffusion routes for potassium ions. The wheel tracks adequately firmed the soil to provide good soil particle-to-particle contact, maintaining better potassium diffusion.

Potassium deficiency in corn: A case study

In June 2021, AGVISE started to receive plant and soil samples to diagnose suspected potassium deficiencies in various crops. This corn example from west central Minnesota included plant and soil samples collected in the good and poor areas of the field. The leaf K concentration was 0.59% in the good and 0.52% in the poor area. For comparison, the corn leaf K sufficiency range at this growth sage should be 2-3% K. The corresponding soil samples had soil test K at 148 ppm in the good and 140 ppm in the poor area. The soil test K critical level for corn is 150-200 ppm, and the farmer had applied 50 lb/acre K2O broadcast + incorporation, which is very close to the university sufficiency guideline for corn. Although the farmer more or less did everything right for a normal rainfall year, drought conditions have reduced potassium availability to the point where potassium deficiency symptoms were apparent and visible.

One week after the plant and soil samples were collected, the field received an inch of rain, and the potassium deficiency symptoms disappeared! The entire corn field is green now. It is amazing what a little water will fix.

Potassium deficiency in corn confirmed with plant and soil analysis. Potassium-deficient corn plant (left) displays chlorosis and necrosis of the outer leaf margin and wavy leaf edge. Plant and soil samples were collected June 2021 in west central Minnesota.

Correcting the problem

So, what do you do next? Do you try to apply an in-season rescue potassium fertilizer application? You still need rain to water in any fertilizer applied to the soil surface. If you had applied an adequate amount of potassium fertilizer before planting, then the appropriate decision is to wait for rain to improve soil and fertilizer potassium availability. However, some people may not have applied enough potassium initially. In these cases, a rescue application of 60 lb/acre K2O broadcast (100 lb/acre potash, 0-0-60) followed by some rain should correct the symptoms. Do not skimp with anything less because you are already behind the eight-ball and you will need that much material to cover the soil surface adequately and affect enough individual corn plants. In NDSU research (2014-2016), an uncorrected potassium deficiency in corn could cost 20-30 bushel/acre compared to corn receiving adequate potassium fertilizer.

For liquid materials, potassium acetate and potassium thiosulfate could be dribbled between the rows, but the potassium rate will need to be similar to the dry potassium fertilizer rate and cost will likely be greater. Remember, potassium is something required in large quantities, not something corrected with a small application of 5-10 lb/acre K2O.

There is no way we could have planned for the very dry conditions that are exacerbating potassium deficiency symptoms across the region. For the future, the best preventative strategy is precision soil sampling (grid or zone) and fertilizing accordingly. It is important to identify and address those parts of fields where potassium may be limiting crop yield potential and spend fertilizer dollars where needed.